Uterine Rupture and Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE)

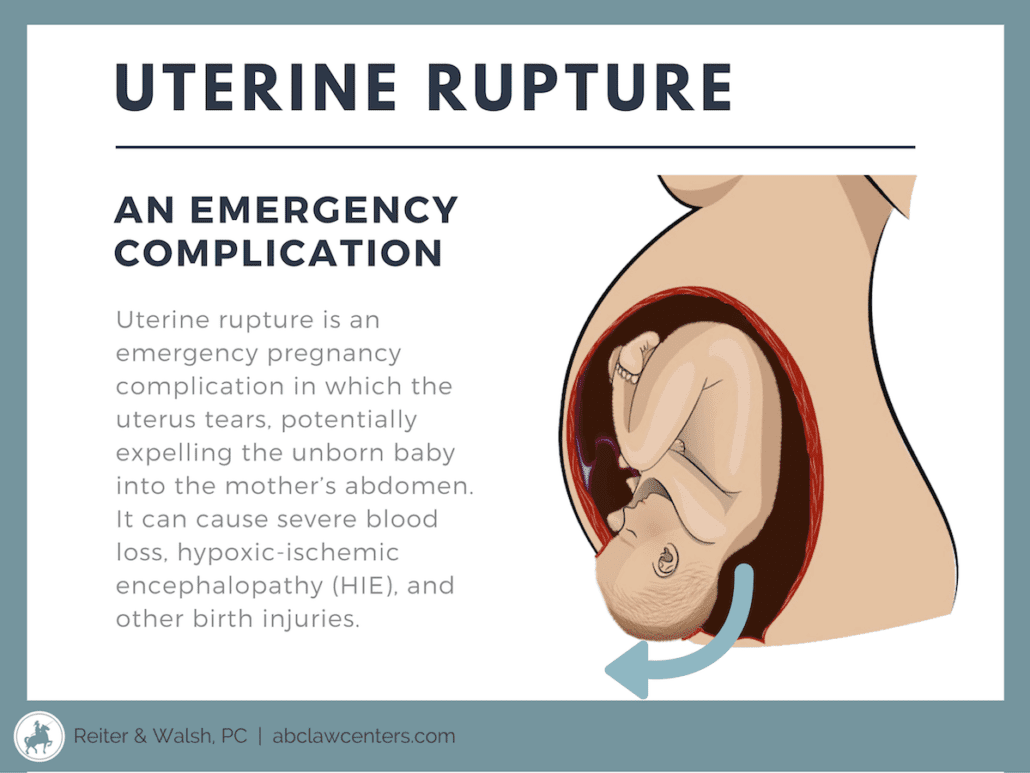

Uterine rupture occurs when, during pregnancy, labor, or delivery, there is a tear in the uterus resulting from pressure. The uterus can rupture throughout some or all of its layers, compromising the fetus’ oxygen supply and causing severe bleeding in the mother (1). Uterine rupture often causes the baby to move into the mother’s abdomen when it is time to deliver. Uterine rupture is most common among women undergoing TOLAC (trial of labor after cesarean) or VBAC (vaginal birth after cesarean) deliveries. It usually occurs because the scars from previous C-sections or uterine or abdominal surgeries tear during labor (1).

Complications of a uterine rupture

The uterus encircles the baby and the amniotic fluid. The placenta is attached to the inside of the womb, and the umbilical cord arises from the placenta. The path of oxygen-rich blood is as follows: uterine vessels to placental vessels to umbilical vein to the baby. Certain vessels of the uterus and placenta are part of what’s termed the uteroplacental circulation, and this circulation brings the blood to the umbilical vein.

If the uterus ruptures, the baby can become severely deprived of oxygen (birth asphyxia) and develop a brain injury called hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), which can cause seizures, cerebral palsy, developmental delays, and more. If a uterine rupture occurs when the baby is premature, the birth asphyxia may cause injury to the basal ganglia and watershed, which is a brain injuries characterized by death and damage of the brain’s tissues.

The complications of a uterine rupture depend on the duration of time between its diagnosis and delivery (2). Because of this, it is imperative that medical professionals monitor labor, quickly diagnose uterine ruptures, and deliver immediately. According to a study by A.S. Leung, significant neonatal morbidity was found in cases of uterine rupture when delivery happened more than 18 minutes after prolonged deceleration (3,4).

A ruptured uterus can lead to fetal complications such as birth asphyxia and neonatal death (2). When a uterine rupture occurs, roughly six percent of babies die (3).

Birth asphyxia

The location and extent of the tear and the baby’s reserves play a role in how severe the birth asphyxia will be. With a severe uterine rupture, the baby may also end up outside the womb and in the mother’s abdomen. Regardless of the extent of the rupture, the baby must be delivered by emergency C-section as soon as a ruptured uterus occurs in order to prevent a lack of oxygen to the baby’s brain.

A ruptured uterus can cause the baby to experience birth asphyxia by the following mechanisms:

- The tear causes the mother to lose so much blood that she is unable to deliver adequate oxygen-rich blood to the baby. The mother may even have such a severe hemorrhage that she goes into shock (blood pressure is severely low), which is life-threatening for the mother and baby.

- The rupture is at or very close to the placenta and it severs vessels involved in uteroplacental circulation, thereby severely reducing the amount of blood going to the baby.

- The rupture affects the placenta. Placental abruption and uterine rupture can occur together. One study found that 18% of uterine ruptures occurred when placental abruption was present and the uterus was unscarred.

- If the baby starts to move into the mother’s abdomen when the uterus is ruptured, many serious medical complications can occur, such as the umbilical cord becoming stretched, compressed, or torn.

Maternal complications

A ruptured uterus can lead to maternal complications such as severe blood loss/hemorrhage, need for hysterectomy, and maternal death (2). About 1% of mothers who experience a ruptured uterus die (3).

Risk factors for uterine rupture

The following are risk factors for uterine rupture:

- Uterine scars: Only 13% of all uterine ruptures occur to unscarred uteri (5). The types of scars that can increase the risk of uterine rupture include the following:

- Scar from a C-section (2)

- High vertical or fundal hysterotomy scar (1)

- Uterine perforation scar: This can occur as a result of any complication involving the uterus and transcervical procedures.

- Myomectomy or metroplasty scar: These scars are from the removal of fibroids in the uterus.

- Scar from the previous repair of a ruptured uterus.

During pregnancy, imaging of scars should be performed. A thin scar or defect should cause the physician to worry about a possible uterine rupture during labor as well as during pregnancy.

Most uterine ruptures occur because a scar from a previous C-section is present. Some of these involve classical C-section scars, which are longitudinal (across the abdomen), upper segment scars. These scars can not only rupture during labor and delivery but also during pregnancy. Rupture of lower segment C-section scars usually takes place during labor.

The rupture of an unscarred uterus is rare, with an estimated occurrence of between 1/5700 and 1/20000 pregnancies (5). A rupture in an unscarred uterus has been attributed to trauma (as in an accident or a fall), weakness in the middle layer of the uterine wall (which functions to induce contractions), disorders of the collagen matrix, and abnormal architecture of the uterine cavity (5). Overdistention of the uterine cavity (e.g., carrying a large baby or multiple babies) is the major physical factor in these cases of rupture. Labor that takes longer than expected due to slow cervical dilation can place prolonged stress on the uterine wall, with the eventual loss of the wall’s integrity.

- Previous uterine rupture (1)

- Grand multiparity: when the mother has given birth 5 or more times (2).

- Labor after C-section: The incidence of uterine rupture in women who are pursuing a VBAC is 0.78% and in women who undergo planned repeat cesarean is 0.22% (1).

- Induction: The incidence of uterine rupture is higher in women who are pursuing a VBAC with induction (1). This is especially true when Pitocin and Cytotec are used (6).

- Malpresentation: This is when the baby is not in the normal head-first position. Malpresentations include brow, face, breech and shoulder presentations (2).

- Post-term labor: Labor past 40 weeks (1)

- Recent delivery (within less than 18-24 months) (1)

- More than one previous cesarean delivery (1)

- Singlelayer uterine closure in prior C-section, especially if locked (1)

- Macrosomia or a baby that is large for gestational age (LGA) (over 4000 grams) (1)

- Multiple fetuses (twins, triplets, etc.)

- Labor dystocia (difficult labor), particularly at advanced gestation

- Certain obstetric maneuvers, such as internal version (physician’s adjustment of the baby’s position in the womb by placing one hand in the mother’s vagina and the other on her abdomen)

- Extraction of a baby in breech presentation (2)

Preventing uterine rupture

Experts emphasize that the best way to prevent uterine rupture is to carefully choose which patients are at low risk and through prophylaxis; physicians must be aware of the mother’s past medical history and must closely watch her during pregnancy and labor. Great effort must be made in diagnosing even minor degrees of CPD or malpresentation, and in treating grand multiparity and other risk factors, especially placental abruption. Mothers with risk factors should be attended to and treated in a special high-risk intensive care zone in the labor department by specially trained physicians and personnel. Difficult operative deliveries should not be attempted, and instead, delivery by C-section should take place.

A vaginal birth after C-section (VBAC) should be attempted only by skilled and prepared professionals and with the mother’s informed consent.

VBAC should only be pursue for a mother who has had a previous transverse, lower-uterine segment C-section for a non-recurring condition, and only after a very careful assessment has been made by the physicians with a determination that vaginal delivery would be favorable. Informed consent from the mother is crucial, and this involves discussing all the risks of a VBAC.

Signs and symptoms of uterine rupture

It is critical for the medical team to closely monitor a mother and baby during labor and delivery – and throughout pregnancy – so that dangerous conditions such as uterine rupture can be promptly treated.

Signs and symptoms of a ruptured uterus include the following (1, 3):

- Abnormal fetal heart rate (FHR) : non-reassuring heart tracings, fetal heart rate decelerations

- Vaginal bleeding or hemorrhaging

- Sudden abdominal pain

- Changes in contraction patterns

- Baby recedes back into the birth canal (loss of station)

- Hemodynamic instability (blood pressure and heart rate problems)

- Hematuria if the rupture extends into the bladder

Non-reassuring fetal heart tones on the heart monitor are the most common and often the only signs of uterine rupture. In most cases, signs of fetal distress will appear before pain or bleeding. It is critical that physicians pay close attention to the fetal heart monitor and be prepared to perform an emergency C-section.

When uterine rupture is present, a prompt delivery by emergency C-section must occur. Moreover, severe abdominal pain, fetal heart rate abnormalities, and maternal hemodynamic instability usually require emergency C-section regardless of their cause (1).

Management of uterine rupture

Before labor

Uterine rupture may be suspected before delivery because of the signs and symptoms above (1). If this is the case, a C-section will usually be planned. A C-section is normally planned in the case of those symptoms, even if a uterine rupture is not diagnosed.

During labor

If a uterine rupture occurs during labor, doctors will need to perform an emergency C-section immediately (1). The goals of the surgery is to deliver the baby safely, control hemorrhage in the mother, repair the uterus, identify damage to other organs, and minimize post-surgical morbidity. In some cases, however, the doctor must perform a hysterectomy, of the complete removal of the uterus.

Delivery

A fast delivery is imperative in cases of uterine rupture in order to avoid damage to both mother and baby. The delivery should occur within 18 minutes of prolonged deceleration in order to avoid significant neonatal morbidity (4).

Long-term outcomes of a mismanaged uterine rupture

When uterine rupture causes birth asphyxia, this may lead to permanent brain damage and a variety of disabilities. These include:

- Neurological impairment

- hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- cerebral palsy

- developmental delays

- Permanent brain injury

Our Experience | Uterine Rupture and hypoxic-Ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) Cases

Birth injury cases require specific, extensive knowledge of both law and medicine. In order to achieve the best results, our team at ABC Law Centers believes it’s critical to specifically and exclusively handle birth injury cases. With over 100 years of joint legal experience, our team has the education, qualifications, results, and accomplishments necessary to succeed. We’ve handled cases involving dozens of different complications, injuries, and instances of medical malpractice related to obstetrics and neonatal care. Our clients hail from all over the United States.

Contact our birth injury attorneys and legal nurses with any questions you may have. We do not charge any fees for our legal processes unless we win!

- Free Case Review

- Available 24/7

- No Fee Unless We Win

Birth injury attorneys discuss uterine rupture, HIE (birth asphyxia) and birth injuries

Watch a video of uterine rupture attorneys Jesse Reiter and Rebecca Walsh discussing birth asphyxia and how this can cause severe birth injuries.

Featured Videos

Posterior Position

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE)

Featured Testimonial

What Our

Clients Say…

After the traumatic birth of my son, I was left confused, afraid, and seeking answers. We needed someone we could trust and depend on. ABC Law Centers was just that.

- Michael

Helpful resources

- Landon, M. B. (n.d.). Uterine rupture: After previous cesarean delivery. Retrieved February 23, 2019, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/uterine-rupture-after-previous-cesarean-delivery

- Revicky, V., Muralidhar, A., Mukhopadhyay, S., & Mahmood, T. (2013). A Case Series of Uterine Rupture: Lessons to be Learned for Future Clinical Practice. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology of India, 62(6), 665-73.

- Uterine Rupture: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment. (n.d.). Retrieved February 23, 2019, from https://www.healthline.com/health/pregnancy/complications-uterine-rupture#treatment

- Leung, A. S., Leung, E. K., & Paul, R. H. (1993, October). Uterine rupture after previous cesarean delivery: Maternal and fetal consequences. Retrieved February 27, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8238154

- Smith, J. F., & Wax, J. R. (n.d.). Uterine rupture: Unscarred uterus. Retrieved February 26, 2019, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/uterine-rupture-unscarred-uterus#H24771926

- Toppenberg, K. S., & Block, W. A. (2002, September 01). Uterine Rupture: What Family Physicians Need to Know. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2002/0901/p823.html